See also

The complete source code of this example can be found in

tutorial/graphene.py

In the following example, we are going to calculate the conductance through a graphene quantum dot with a p-n junction and two non-collinear leads. In the process, we will touch all of the topics that we have seen in the previous tutorials, but now for the honeycomb lattice. As you will see, everything carries over nicely.

We begin by defining the honeycomb lattice of graphene. This is

in principle already done in kwant.lattice.honeycomb, but we do it

explicitly here to show how to define a new lattice:

graphene = kwant.lattice.general([(1, 0), (sin_30, cos_30)],

[(0, 0), (0, 1 / sqrt(3))])

a, b = graphene.sublattices

The first argument to the general function is the list of

primitive vectors of the lattice; the second one is the coordinates of basis

atoms. The honeycomb lattice has two basis atoms. Each type of basis atom by

itself forms a regular lattice of the same type as well, and those

sublattices are referenced as a and b above.

In the next step we define the shape of the scattering region (circle again)

and add all lattice points using the shape-functionality:

def make_system(r=10, w=2.0, pot=0.1):

#### Define the scattering region. ####

# circular scattering region

def circle(pos):

x, y = pos

return x ** 2 + y ** 2 < r ** 2

sys = kwant.Builder()

# w: width and pot: potential maximum of the p-n junction

def potential(site):

(x, y) = site.pos

d = y * cos_30 + x * sin_30

return pot * tanh(d / w)

sys[graphene.shape(circle, (0, 0))] = potential

As you can see, this works exactly the same for any kind of lattice. We add the onsite energies using a function describing the p-n junction; in contrast to the previous tutorial, the potential value is this time taken from the scope of make_system, since we keep the potential fixed in this example.

As a next step we add the hoppings, making use of

HoppingKind. For illustration purposes we define

the hoppings ourselves instead of using graphene.neighbors():

hoppings = (((0, 0), a, b), ((0, 1), a, b), ((-1, 1), a, b))

The nearest-neighbor model for graphene contains only

hoppings between different basis atoms. For this type of

hoppings, it is not enough to specify relative lattice indices,

but we also need to specify the proper target and source

sublattices. Remember that the format of the hopping specification

is (i,j), target, source. In the previous examples (i.e.

Matrix structure of on-site and hopping elements) target=source=lat, whereas here

we have to specify different sublattices. Furthermore,

note that the directions given by the lattice indices

(1, 0) and (0, 1) are not orthogonal anymore, since they are given with

respect to the two primitive vectors [(1, 0), (sin_30, cos_30)].

Adding the hoppings however still works the same way:

sys[[kwant.builder.HoppingKind(*hopping) for hopping in hoppings]] = -1

Modifying the scattering region is also possible as before. Let’s do something crazy, and remove an atom in sublattice A (which removes also the hoppings from/to this site) as well as add an additional link:

del sys[a(0, 0)]

sys[a(-2, 1), b(2, 2)] = -1

Note again that the conversion from a tuple (i,j) to site is done by the sublattices a and b.

The leads are defined almost as before:

# left lead

sym0 = kwant.TranslationalSymmetry(graphene.vec((-1, 0)))

def lead0_shape(pos):

x, y = pos

return (-0.4 * r < y < 0.4 * r)

lead0 = kwant.Builder(sym0)

lead0[graphene.shape(lead0_shape, (0, 0))] = -pot

lead0[[kwant.builder.HoppingKind(*hopping) for hopping in hoppings]] = -1

# The second lead, going to the top right

sym1 = kwant.TranslationalSymmetry(graphene.vec((0, 1)))

def lead1_shape(pos):

v = pos[1] * sin_30 - pos[0] * cos_30

return (-0.4 * r < v < 0.4 * r)

lead1 = kwant.Builder(sym1)

lead1[graphene.shape(lead1_shape, (0, 0))] = pot

lead1[[kwant.builder.HoppingKind(*hopping) for hopping in hoppings]] = -1

Note the method vec used in calculating the

parameter for TranslationalSymmetry. The latter expects a

real-space symmetry vector, but for many lattices symmetry vectors are more

easily expressed in the natural coordinate system of the lattice. The

vec-method is thus used to map a lattice vector

to a real-space vector.

Observe also that the translational vectors graphene.vec((-1, 0)) and

graphene.vec((0, 1)) are not orthogonal any more as they would have been

in a square lattice – they follow the non-orthogonal primitive vectors defined

in the beginning.

Later, we will compute some eigenvalues of the closed scattering region without leads. This is why we postpone attaching the leads to the system. Instead, we return the scattering region and the leads separately.

return sys, [lead0, lead1]

The computation of some eigenvalues of the closed system is done in the following piece of code:

def compute_evs(sys):

# Compute some eigenvalues of the closed system

sparse_mat = sys.hamiltonian_submatrix(sparse=True)

evs = sla.eigs(sparse_mat, 2)[0]

print evs.real

Here we use in contrast to the previous example a sparse matrix and the sparse linear algebra functionality of SciPy.

The code for computing the band structure and the conductance is identical to the previous examples, and needs not be further explained here.

Finally, in the main function we make and plot the system:

def main():

pot = 0.1

sys, leads = make_system(pot=pot)

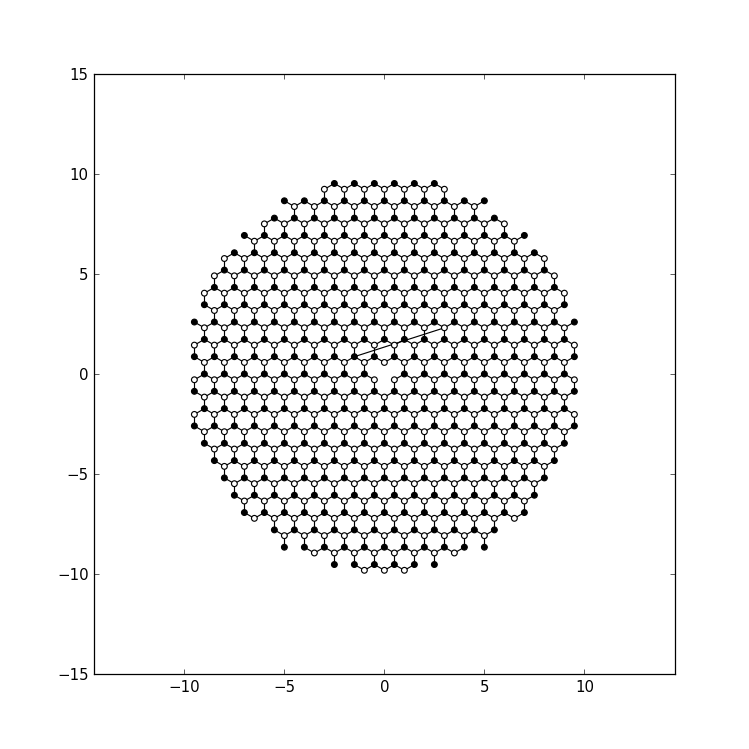

# To highlight the two sublattices of graphene, we plot one with

# a filled, and the other one with an open circle:

def family_colors(site):

return 0 if site.family == a else 1

# Plot the closed system without leads.

kwant.plot(sys, site_color=family_colors, site_lw=0.1, colorbar=False)

We customize the plotting: we set the site_colors argument of

plot to a function which returns 0 for

sublattice a and 1 for sublattice b:

def family_colors(site):

return 0 if site.family == a else 1

The function plot shows these values using a color scale

(grayscale by default). The symbol size is specified in points, and is

independent on the overall figure size.

Plotting the closed system gives this result:

Computing the eigenvalues of largest magnitude,

compute_evs(sys.finalized())

should yield two eigenvalues equal to [ 3.07869311,

-3.06233144].

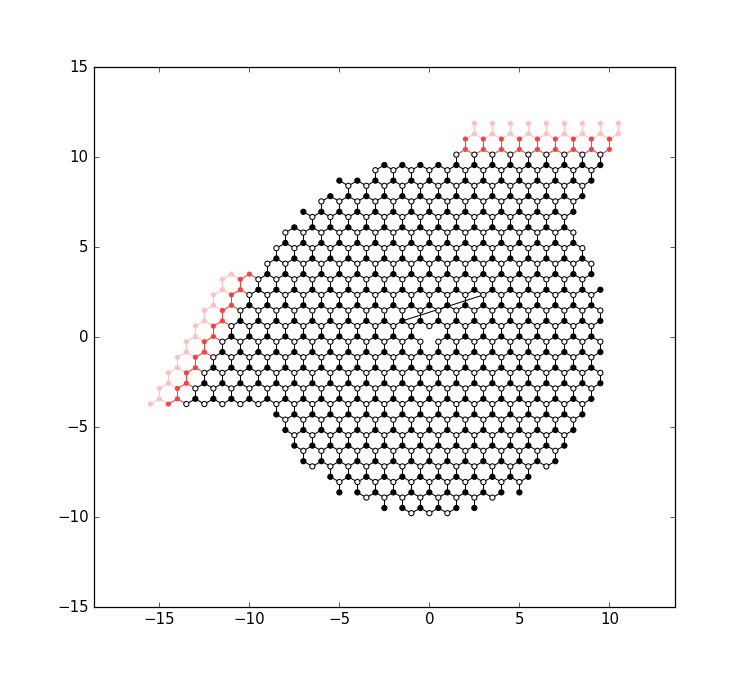

The remaining code of main attaches the leads to the system and plots it again:

It computes the band structure of one of lead 0:

showing all the features of a zigzag lead, including the flat edge state bands (note that the band structure is not symmetric around zero energy, due to a potential in the leads).

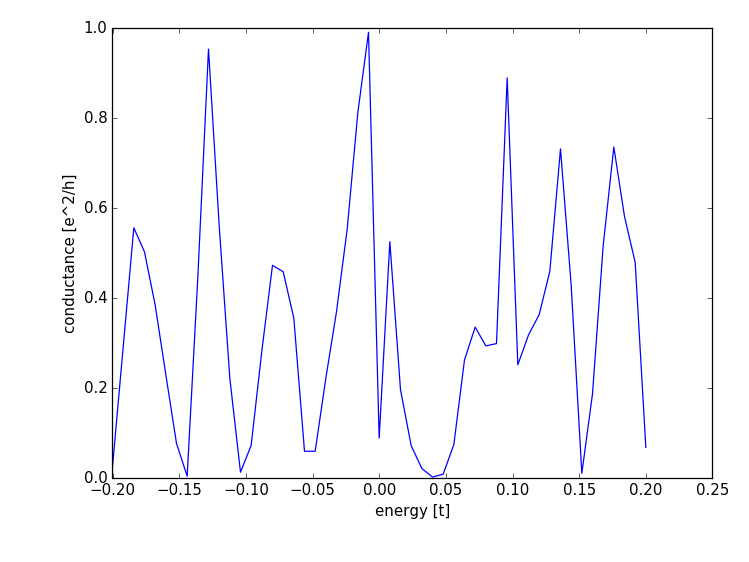

Finally the transmission through the system is computed,

showing the typical resonance-like transmission probability through an open quantum dot

In a lattice with more than one basis atom, you can always act either on all sublattices at the same time, or on a single sublattice only.

For example, you can add lattice points for all sublattices in the current example using:

sys[graphene.shape(...)] = ...

or just for a single sublattice:

sys[a.shape(...)] = ...

and the same of course with b. Also, you can selectively remove points:

del sys[graphene.shape(...)]

del sys[a.shape(...)]

where the first line removes points in both sublattices, whereas the second line removes only points in one sublattice.